Why look at animals? Art for the rights of non-human lives

Annika Kahrs, Playing to the Birds, 2013. Photo: Paris Tavitian.

Nearly fifty years later, Berger’s writings are the inspiration for Why Look at Animals? A Case for the Rights of Non-Human Lives, a seminal exhibition at EMST, the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Athens. Curated by the Museum’s artistic director Katerina Gregos, the exhibition’s focus sits firmly on animal rights, highlighting the urgent need to both recognise and defend non-human animals in an anthropocentric world that exploits and brutalises them. Originally from Athens, Gregos is a curator, lecturer and writer with extensive experience in the international art world, serving as director for both private and public institutions. Her curatorial practice consistently explores the relationship between art, society and politics with a particular view on questions of democracy, human rights, economy, ecology and crisis.

“I first read Berger’s essay many years ago, and I remember being profoundly struck — not just intellectually, but emotionally,” reflects Gregos, by email. “It was one of those rare texts that re-arranges how you see the world. Berger’s clarity, his tenderness toward animals, and his ability to articulate the quiet tragedy of their disappearance from our lives stirred something visceral in me. There was a deep sense of sadness, but also anger; an awareness of the enormity of what had been lost - and is still being lost - and of how complicit we all are in that loss.

“Berger’s phrase ‘Everywhere animals disappear’ made me reflect on how easily we accept the absence of animals from our daily lives while simultaneously consuming them — visually, physically, culturally,” she continues. “There was a sense of shame, but also urgency. But what I felt most was a kind of moral awakening, a desire to respond, not with guilt, but with responsibility. In many ways, this exhibition is the long echo of that first encounter with Berger’s words.”

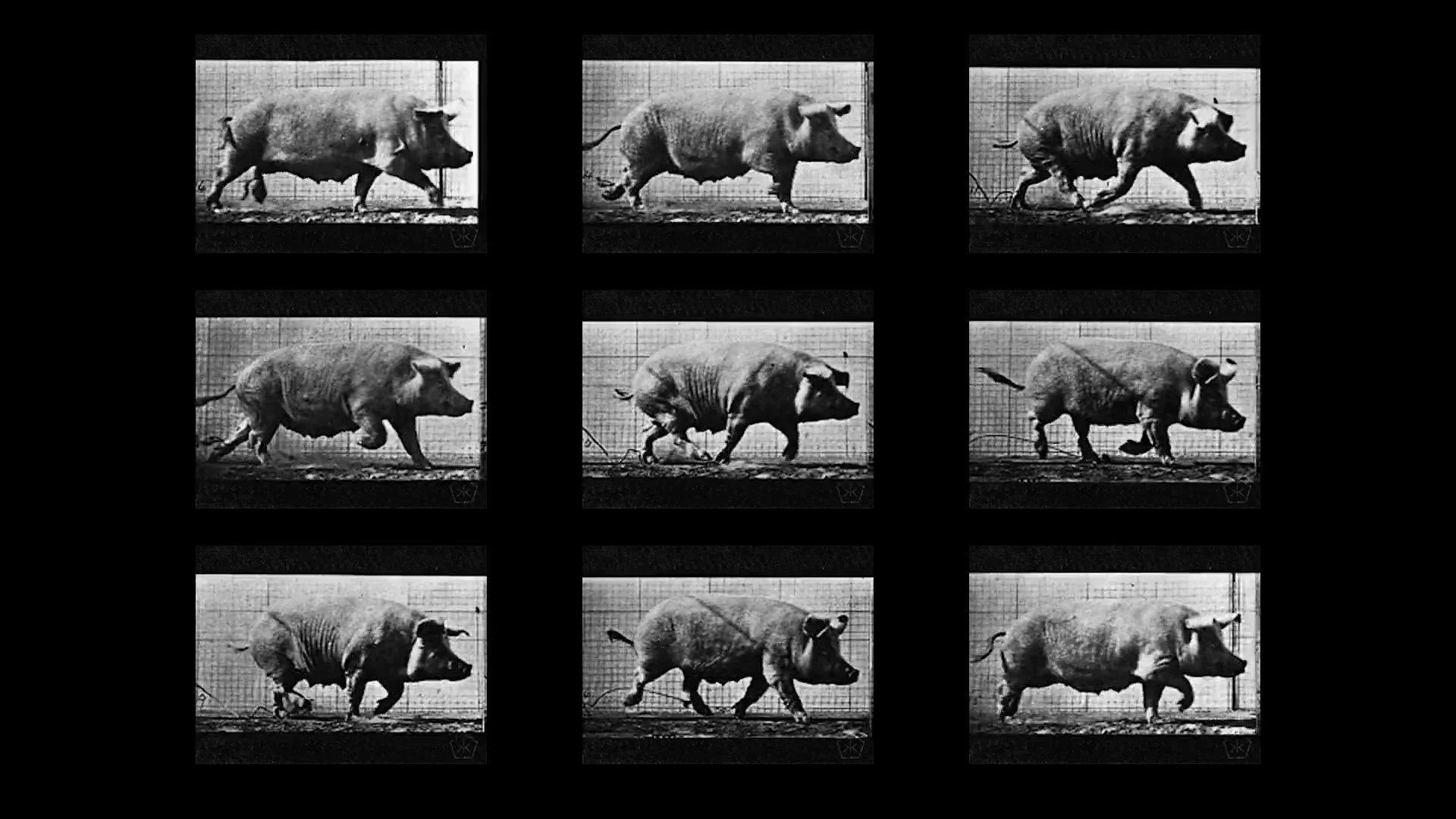

Animals have always been subjects of art; “the first subject for painting was animal. Probably the first paint was animal blood,” muses Berger. But the filter has always been human. Animals have painted as property; offered as symbols of hope, love, peace, or courage; wrestled to the ground as mythical demons and prey; or sketched as anatomical studies. EMST’s exhibition looks beyond the human lens towards our species’ fractured relationship with animals itself. Over seven floors, 60 artists from 30 countries spotlight the lives, rights, well-being and sentience of animals, while asking urgent ecological and ethical questions surrounding the human-animal relationship. It’s a sprawling, moving, compassionately curated show; long overdue, much needed.

Industrialised into abstraction

That the exhibition is so extensive is testament to its timeliness. Few could claim that all is well in the animal kingdom; fewer still would say that humanity hasn’t had a leading role to play in that distress. Only 2% of mammals alive today are wild; 60% are farmed. Those two figures are tragically interlinked. In the past decades, 73 per cent of the world’s wild creatures have disappeared - to be replaced with billions of others, bred into existence to be brutalised and consumed. Yet, as a subject for discussion, let alone outrage, the extermination is barely acknowledged. For governments, animals are an irritation; for businesses, they are resources. Even agencies working for climate and nature find the ‘animal issue’ difficult to address, preferring instead to deal with partial definitions of social justice and equity.

Ang Siew Ching, High-Rise Pigs, 2025. Photo: Paris Tavitian.

Why Look at Animals? brings nonhuman animals back into the centre of human consciousness - where they should have been all along. Approaches differ. Some artists address sites of systemic violence: the egregious system of factory farming, in which 150 billion mammals are killed as food every year; animal testing, which kills up to 150 million; and ecological displacement which loses trillions to natural and manmade disaster. The monstrous Zhongxin Kaiwei Pig Building in Hubei is the starting point for Singaporean artist Ang Siew Ching’s short film, High-Rise Pigs (2025). As the world’s largest single-building pig farm, the 26-storey skyscraper has the capacity to slaughter 1.2 million pigs (the country’s favourite ‘meat’ animal) per year, obscuring their suffering beneath veneers of efficiency such as air-conditioned pens, enhanced bio-security and mechanized slaughter systems. Welcome to the farms of the future.

Rossella Biscotti’s installation, Clara (2016) is named for the female Indian rhinoceros who criss-crossed Europe in the mid-eighteenth century as curiosity and attraction. Biscotti reconstructs Clara’s weight in bricks stamped with her image. A pile of tobacco refers to the drug used to tranquilise Clara during long voyages and performances; an appalling reminder of her distress. “Clara is devastating precisely because of its restraint,” writes Gregos. “It doesn’t scream — it whispers. Through minimalist means, Biscotti explores the cruelty embedded in bureaucratic logistics, in state-sanctioned display, in the presumed right to transport, tranquilise, and exhibit another being. Clara’s suffering is not theatrical; it’s administrative. And that’s what makes it so chilling. Clara’s disorientation becomes a metaphor for the systemic erasure of animal agency in human spectacle.”

Other artists reveal subtler forms of appropriation. In Playing to the Birds (2013) by Annika Kahrs, a pianist in coat and tails performs Franz Liszt’s Legends No. 1: Saint Francis of Assisi’s Sermon to the Birds (1863) to an audience of caged songbirds. The little birds respond with chirrups and trills, the gift of (bird)song returned to them through human creativity. Again, pathos speaks: in what other concert are audience members those who have been separated from their families and caged, only to sing helplessly to the imitation of their own voices?

But there is also joy in Why Look at Animals?. It is present in the squat, tactile figurines by Greek sculptor Euripides Vavouris, every shaped line a testament to his love for his subjects. And it is present in eco-feminist Marta Roberti’s explorations of goddess iconography. Roberti’s Self-portrait as Saint Olivia lying on jaguar (2023) speaks not only to our yearning for renewed kinship with animals but also to the elation possible, should humans and more-than-human animals ever live in harmonious coexistence.

Oussama Tabti, Homo-Carduelis, 2022. Photo: Paris Tavitian

Are there pieces that resonate for Gregos? “Each one reveals a different facet of the human-animal relationship,” she writes. “But Oussama Tabti’s Homo-Carduelis (2022) continues to haunt me. From a distance, it appears delicate: rows of birdcages suspended like a miniature city, each housing not a bird but a speaker. What emerges is not birdsong, but human voices imitating it — an eerie choir of longing. The installation is both poetic and unsettling, a reflection on our desire to possess freedom even as we destroy it. It implicates us. We sing of the goldfinch as a symbol of love and liberty while endangering it through our need for control.”

She also highlights the work of Tatiana Pers, for its “radical tenderness.” The Italian academic and activist regularly “collapses the space between art, life and ethics”, says Gregos, inviting participants into dynamic engagement with her projects. In Art History (ongoing), Pers exchanges farmed animals destined for slaughter for paintings; so far, she has helped 300 rescued animals to sanctuary. In The Age of Remedy (2020), dinner plates are turned into “sites of contract and conscience.” Participants buy a plate but must also sign a contract to stop eating animal products while using it. Hope springs eternal: Pers created 7,781,533,400 contracts, the estimated human population at the time the work was conceived. “The first contract, signed with her son, Ivan, is heartbreakingly intimate,” writes Gregos. “These works don’t moralise — they propose a quiet revolution of values, asking: what are we willing to trade for life, and what does that say about us?”

Latent throughout the exhibition is the question: why do we cherish some animals while allowing others - equally intelligent, curious and playful - to be so terribly treated? “This contradiction is precisely the moral blind spot the exhibition seeks to illuminate,” writes Gregos. “We’ve industrialised animals into abstraction. We encounter them through packaging, metaphors, images, memes — not as sentient beings with subjective experiences. The systems we live in depend on keeping animals hidden: in factory farms, labs, and slaughterhouses. Our cognitive dissonance is maintained by convenience and disconnection. Recognising animals as individuals demands we undo centuries of philosophical, theological, and economic frameworks that treat them as lesser lives. That undoing is both urgent and profoundly uncomfortable.”

Creating the collective

Finding like-minded artists was a lens shift rather than an unearthing. “What became clear early on — and what surprised even some critics — was that many artists, often associated with entirely different themes, had long been engaging with animals in deeply thoughtful ways. It’s just that their work hadn’t always been framed through the lens of animal rights or multispecies ethics,” reflects Gregos.

At the same time, “there was a sense of shared urgency, but also relief that an institution was finally centering this issue — not as a secondary concern, but as a serious philosophical and curatorial framework. Many artists welcomed the opportunity to show this side of their work in a new light, while galleries were eager to support a project that resonates so clearly with current ecological and ethical discourses. It felt less like launching a new conversation, and more like amplifying one that has long been quietly underway.”

Igor Grubić, Ingresso Animali Vivi (Live Animal Entrance), 2023.

Animal intelligence, speciesism, ecological interconnectedness, exploitation and the human-animal divide: exploring these themes was always going to be sticky. “The most pressing challenge was curating without slipping into didacticism,” says Gregos. “The subject is urgent, emotionally charged, and ethically complex but art must remain a space of ambiguity and nuance, not propaganda. Balancing advocacy with aesthetics required care. The works on view do not offer simplistic binaries. Instead, they surface the everyday normalisation of cruelty, often hidden in plain sight. The aim is not to accuse but to unsettle – to ask: how can love and violence co-exist so seamlessly in our relationship with animals? And how can we begin to change the inherent contradiction and hypocrisy that characterises our relationship to animals?”

Then, there was the curatorial imperative to de-centre Western narratives. “At EMST, part of our mission is to challenge dominant narratives and amplify under-represented perspectives,” writes Gregos. “Animal ethics are not universal; they’re culturally contingent. So it was important not only to include well-known artists, but also those working from diverse geographies and worldviews— particularly Indigenous, postcolonial, and non-Western approaches to interspecies coexistence, that offer radically different ontologies of interspecies life. What emerged was not a niche interest, but a shared, global urgency.”

Another challenge was representation: “How do we visualise animal suffering without sensationalising it? How do we speak for beings who cannot speak, without speaking over them?” Gregos continues. The museum has made a deliberate decision to avoid graphic violence, what most activists would describe as the defining aspect of humanity’s relationship with animals. “There’s already an overwhelming amount of imagery that desensitises or retraumatises,” explains Gregos. “Instead, the exhibition uses implication, suggestion, and poetics. We want viewers to engage, not shut down. Violence is present — but it is mediated through form, concept, and atmosphere. The goal is not shock, but critical intimacy.”

And yet shock is present, particularly for those already familiar with the scale of animal suffering today. The sense of the animals’ presence in erasure (the pig in the ham sandwich, for example; the cow grieving for her calf in the pint of milk, the slaughtered sheep in the jumper) haunts Ingresso Animali Vivi (Live Animal Entrance) (2023) by Croatian artist Igor Grubić. In the short film, a dog wanders through a former slaughterhouse and its paraphernalia of death. She is shown, watching from doorways, as if seeing past scenes of violence; or crouched, as the animals might have done, to escape attention. Silent, wary, she is the only animal in its history to leave the slaughterhouse alive. It is a devastating reminder of how humans treat our gentlest kin.

Sue Coe, If animals believed in God, the devil would look like a human being, 2009.

In his works The Soul (2025), Mostafa Saifi Rahmouni echoes similar themes, showing lion heads wrapped in plastic, just two of the millions of animals illegally traded each year as pets, parts for traditional medicines and trophies. Rahmouni’s sculpture The Intermediary (2015) is a butcher’s block, elevated to art by its location, its flowing lines created for carving up animal parts. In a work crafted from styrofoam, late German-Iraqi sculptor Lin May Saeed depicts the relationship between humans and animals as War (2006); to even the most casual observer, it feels more like a massacre. Meanwhile, Pers’ The Sleepless Monkeys (2019) refers to a controversial 2019 experiment when Chinese scientists made five little clones of a gene-edited macaque to aid research of circadian rhythm disorders linked to sleep problems, depression and Alzheimer's. Pers paints the young monkeys at night, trying to imagine what the passage of time might be like for someone who has never known a mother’s care, a natural habitat or even the escape of sleep.

For all Gregos tries to avoid didactism, Why Look at Animals cannot help but agitate; it would take a hard heart to absolve itself completely of complicity in the bloodbath. Few make this as explicit as visual essayist Sue Coe, in her lithograph If animals believed in God, the Devil would look like a human being (2004). “In one sentence, Coe captures what entire volumes on speciesism and animal rights have tried to articulate,” writes Gregos. “It’s a searing indictment of human supremacy. It’s not just about cruelty; it’s about the structural domination we exercise over animals — economically, culturally, politically. Coe’s quote encapsulates the moral inversion that allows us to profess love for animals while being complicit in their widespread exploitation. It provokes a necessary discomfort, and that’s precisely the affective tension the exhibition embraces. It’s a mirror we hold up to ourselves — not to condemn, but to compel reflection.”

Culture is changing

Descartes might have thought that nonhuman animals, which he called bêtes-machines, function like mechanical beings but that is largely because they had no way of communicating with him. Recent discoveries in animal sentience have been impossible to ignore. “The discovery of animal sentience has dismantled the last credible justifications for their exploitation,” confirms Gregos. “We now know that animals think, feel, remember, grieve. Sentience is no longer speculative — it’s scientific fact. And recognising sentience means recognising moral obligation. It demands a shift from seeing animals as objects of use to humans to beings with their own intrinsic value, with whom we share a deeply entangled future.”

For all those involved in creating more equitable futures, knowing that Why Look at Animals does not sit in a cultural vacuum is a balm. “The change is happening on multiple fronts — climate science, philosophy, law, activism, and now art,” confirms Gregos. “We’re witnessing the collapse of the old anthropocentric model. The cumulative evidence of interdependence and ecological vulnerability is impossible to ignore. The animal is returning — not as a symbol of nature, but as a subject of rights and responsibilities.” The problem, she says, is that change is slow, countered by those with vested interests in keeping the dominant extractivist, ecocidal model in place.

It is precisely for this reason that transforming our relationship with animals (and transforming it viscerally and deliberately, in the way we live on this planet) is the most radical act that ordinary people can engage in. The intersections of animal destruction with climate, ecological damage and social injustice - areas in which ‘those with vested interests’ continue to profit - are too profound to ignore. “Repositioning animals as subjects, not metaphors, not commodities, invites viewers to rethink the very foundations of their worldviews,” writes Gregos. “Because this shift doesn’t only concern animals; it ripples into how we think about justice, empathy, and power more broadly. Recognising animal subjectivity is a gateway to reimagining ethics beyond the human — a necessary move if we’re serious about addressing climate collapse, extinction, and systemic violence. It’s not about sentimentality. It’s about survival.”

”We are at a precipice: ecologically, ethically, existentially,” she continues. “The way we treat animals is both a symptom and a driver of the wider planetary crisis. Our disconnection from non-human life mirrors our disconnection from the Earth itself. Re-examining this relationship is no longer optional, it’s essential. Not just for the animals, but for our own future.”