Why isn't animal freedom seen as a legitimate freedom struggle?

Standing Rock brought together the largest gathering of Indigenous nations in over a century, joined by military veterans, climate activists and faith leaders in an unprecedented show of solidarity. Image: Protesters at the Standing Rock reservation in North Dakota, in defiance of the oil pipeline project. Photograph: Stephanie Keith/Reuters

This post was first published on Dec 16, 2025 by Natalie Braine, Narrative Power Lead at Project Phoenix. Subscribe to The Project Phoenix Substack page to get more articles like this in your inbox here.

Last year, one of the Project Phoenix team stood in a conference room full of social justice communicators from every movement imaginable – people working for abortion rights, climate justice, racial equality, homelessness and more.

When we shared that our work is focused on animal freedom, this was met with polite smiles and stiff nods from the group, before a woman leaned forward to say: “That’s nice you can focus on animal rights in the UK. Here in the US, we need to work on improving human rights first.”

Most of us have likely heard some version of this: that animal freedom needs to wait in line. But when it comes from people working in social justice, it can feel particularly disheartening – because they would never tell feminists to wait until racism is defeated, or climate activists to pause until poverty is eliminated. Yet somehow, animal freedom is forced to the bottom of the social justice hierarchy – if it’s considered justice work at all.

What struck us wasn’t the dismissal itself. We understand zero-sum thinking – the belief that attention to one issue will detract from another – and that for many people, just the mention of ‘animal freedom’ triggers cognitive dissonance, the uneasy feeling that your actions might contradict your beliefs.

What really struck us was that even as people work to dismantle harmful hierarchies in society, hierarchies can still get unconsciously reproduced in social justice spaces.

Within our own movement, we’re grappling with something similar. Some advocates argue our movement should focus exclusively on ‘animals first’ – that being ‘intersectional’ dilutes our message when billions of animals are killed every year. Others believe we should work in solidarity with other movements, because all oppressions are interconnected.

Both perspectives are understandable and raise valid concerns. But what if the debate itself reveals how deeply we’ve all internalised the very framework we’re trying to dismantle?

How did we get here?

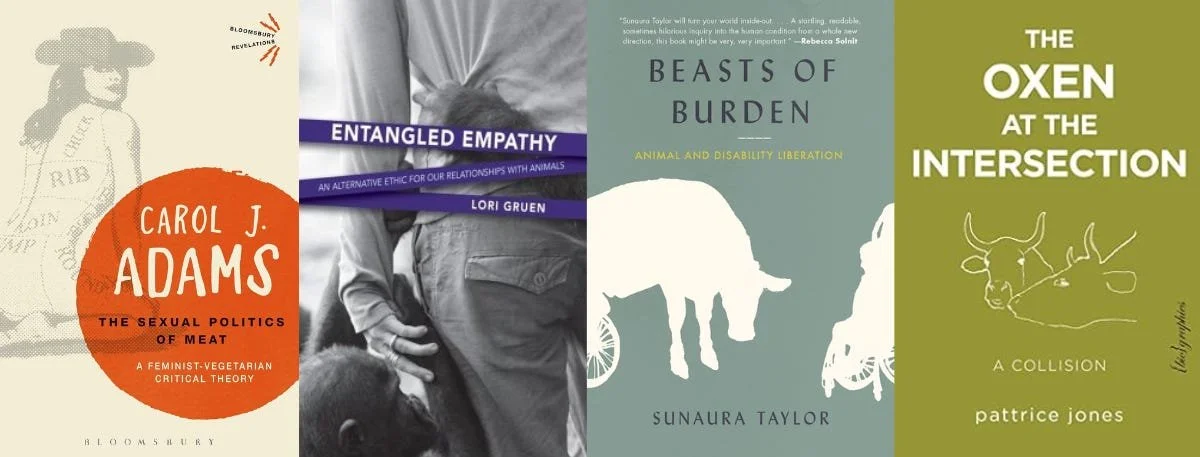

When people think of influential texts in the animal movement, certain names come to mind, including: Peter Singer’s Animal Liberation, Tom Regan’s The Case for Animal Rights and Jonathan Safran Foer’s Eating Animals. Books that have influenced ethical arguments about animal freedom

These works are important and have shaped many of us. They provide powerful ethical arguments, yet they do not fully address a different kind of question: How did billions of humans come to accept the systematic domination and killing of other animals as natural, inevitable, even divinely ordained?

At Project Phoenix, we believe feminist perspectives have been offering deeper answers to this question for decades – yet they remain under-read, even within our own movement.

Feminist perspectives on animal rights offer an intersectional perspective.

Carol J. Adams’ The Sexual Politics of Meat reveals how patriarchal logic commodifies both women’s bodies and animals as meat. Lori Gruen’s Entangled Empathy shows how animal oppression is bound up with other forms of domination. Sunaura Taylor’s Beasts of Burden connects animal liberation with disability justice, showing how ideas of ‘productivity’ and ‘usefulness’ devalue both humans and other animals. Through decades of work, pattrice jones has similarly shown that animal liberation is inseparable from feminist, anti-racist and queer struggles. Books from feminist thinkers that offer an intersectional perspective.

Another writer that has expanded our thinking at Project Phoenix, and also deserves far wider recognition, is Jim Mason, particularly his books An Unnatural Order: The Roots of Our Destruction of Nature and Madness: Lessons From My Family Farm.

Through archaeological, anthropological and historical research, Mason reveals how the domination of our animal cousins created the blueprint for every form of oppression humans have inflicted on each other. His work raises a fundamental question: Is our movement pushing for animal freedom alone, or for a deeper transformation of how humans understand our place in the world?

How it all began

Mason’s research reveals that, for 99% of our species’ existence, humans lived as foragers, seeing other animals as kin – ancestors, teachers, spirit-powers. Women held high status. There was no concept of nature as separate, no hierarchy with humans (and men) at the top.

Then came settled agriculture 10,000 years ago, and with it, the control it required. Other animals shifted from ‘gods’ to ‘goods’; from beings to be honoured to resources to be owned.

Animals became the first form of capital – the Latin ‘capita’ literally means ‘head of cattle’. With their domestication came early forms of human slavery. In ancient Sumeria, the same word was used for castrated male slaves as castrated farmed animals. The techniques of ‘animal husbandry’ – breaking, taming, breeding – became the model for controlling women’s bodies and sexuality.

The same logic that justified animal domination was later weaponised by colonisers, who described Indigenous people as ‘beasts’ and ‘brutes’, requiring white ‘shepherds’. People with darker skin, different customs and unfarmed land were viewed as ‘closer to nature’ and therefore inferior.

Mason and many feminist thinkers suggest that speciesism, sexism, racism and ableism didn’t develop in isolation. They emerged together through shared tactics of domination: creating hierarchies, denying agency, claiming a ‘natural order’.

Understanding these shared patterns isn’t about comparing different struggles; it’s about recognising how oppressive systems reinforce each other, and why dismantling one requires challenging the underlying framework beneath all.

What does this mean for our movement?

This explains why animal freedom remains marginal, even as evidence of the scale and impact of animal exploitation continues to grow. The obstacle is not a lack of facts about animal suffering; it’s the underlying worldview – and the systems built upon it – that frames how people interpret those facts and consider which lives matter.

But worldviews can shift, and they often do when dominant narratives are challenged and replaced by other narratives. And this happens through the stories and messages we repeatedly tell and hear.

The story our movement most often tells focuses on suffering: factory farm conditions, welfare standards breached, numbers killed. All of this is crucial and needs to be communicated. And, as these writers argue, we also need stories that help people understand the interconnection of all oppression – not as abstract theory, but as lived reality. We need stories that communicate what we’ve lost as a species: our deep connection with other humans, other animals, with the rest of nature, and with our shared home. The sense of belonging that sustained humans for 200,000 years – before agriculture taught us that separation and domination were ‘normal, natural, necessary and nice’.

People are still feeling this deep loss of belonging, even if they cannot name it. Many are hungry for reconnection, even as mainstream culture tells us that domination and separation is the only possible relationship with the more-than-human world.

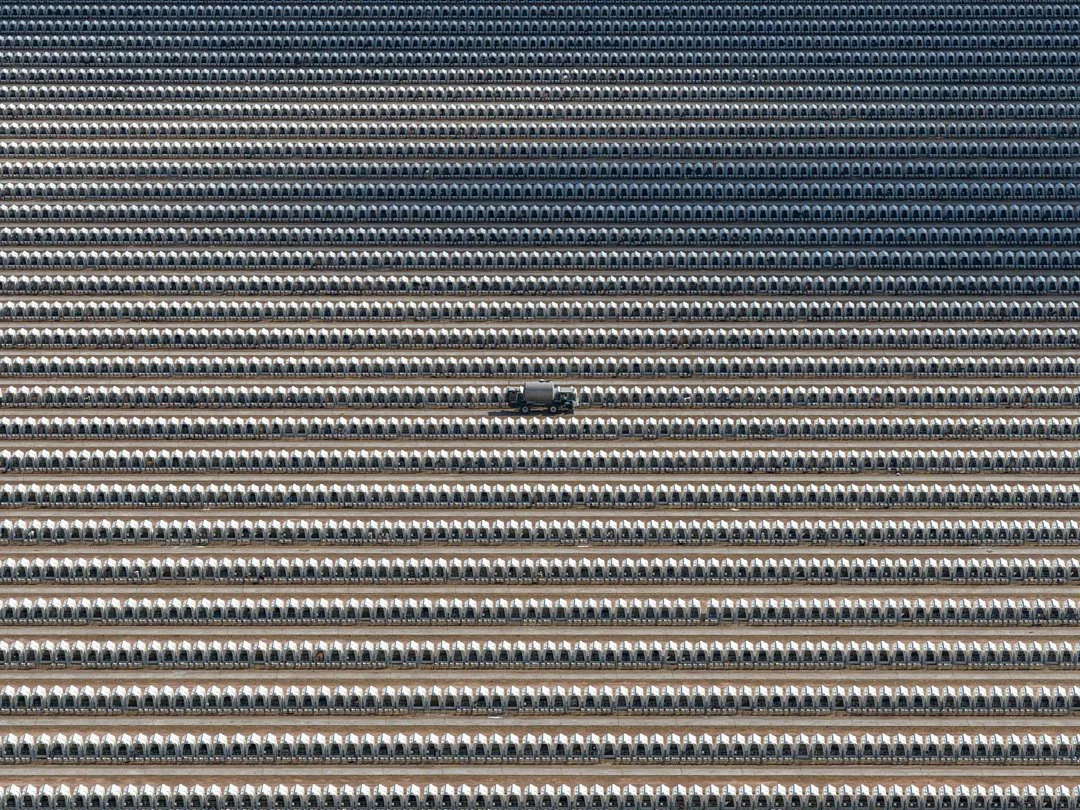

“Our work is all the harder because we’re up against powerful industries and systems that constantly reinforce their narratives.” Image: A milk dispenser truck drives between some of the thousands of calf hutches in a massive dairy farm's yard. Turkey Creek Dairy, Pearce, Arizona, USA, 2023. Ram Daya / We Animals

A deeper story

The work of narrative change is never easy – it’s complex and can take decades. Our work is all the harder because we’re up against powerful industries and systems that constantly reinforce their narratives, as well as further entrench harmful worldviews: capitalism, patriarchy, extraction over reciprocity. And, of course, animal exploitation is embedded in global capitalism, subsidised by governments, protected by law, defended by massive lobbying operations.

Many movements recognise that we need campaigns that can reduce suffering now alongside longer term narrative work that can shift the worldview enabling that harm. If we focus only on immediate harm reduction, we risk addressing symptoms without challenging root causes. If we focus only on long-term narrative change, individuals continue to suffer while we wait for public consciousness to shift. Movements need both strategies, working in tandem. Yet long-term narrative change can often get overlooked and undervalued.

Fortunately, many movements are already engaged in this deeper work. Doughnut Economics, Stories for Life and the Wellbeing Economy Alliance are reimagining economic systems in service to life rather than endless growth.

Indigenous scholars like Robin Wall Kimmerer and Four Arrows speak of returning to reciprocity with the living world. Climate activists increasingly frame their work not only as environmental protection but as recognising our interbeing with all life.

These movements echo what Mason, Adams, Gruen, Taylor and jones have been saying for decades: to weaken the harmful story of separation and strengthen a story of reconnection, we need a compelling story that explains how we got here and where we might go. Just as short-term ‘welfare’ and long-term ‘abolition’ strategies can work together, so too can ‘animals first’ and ‘intersectional’ approaches.

The question is how we can follow different approaches and strategies in ways that strengthen rather than undermine each other. And ultimately how we can tell a deeper, more inspiring story that people can see themselves in: not just a world with less suffering, but with more connection.

Solidarity as strategy

Some within our movement have questioned whether addressing the intersectionality of our issue dilutes our focus. This concern is understandable. The scale and level of animal suffering is incomprehensible. Animals cannot directly advocate for themselves. And if we don’t focus on this issue, who will?

Yet there is growing evidence that solidarity can strengthen our work rather than weaken it.

Consider Animal Rebellion’s decision to collaborate with Extinction Rebellion, despite Extinction Rebellion not focusing on a plant-based food system as part of the wider climate solution. Some animal advocates objected, yet this collaboration helped shift environmental narratives about the impact of farming animals. It elevated animal issues within climate conversations in ways that isolated advocacy might have struggled to achieve. It also encouraged many animal advocates to engage more deeply with entangled environmental issues.

Solidarity has made countless other movements stronger. The unlikely support of lesbian and gay activists for UK miners in the 1980s led to the miners’ union backing LGBTQ+ rights in the Labour party – accelerating legal gains for both. The film Pride dramatised the unlikely collaboration between LGBTQ+ activists and UK miners

When Black communities and environmental groups joined forces in the US, they created the environmental justice movement, exposing how pollution and toxic dumping target marginalised communities. At Standing Rock, Indigenous water protectors reframed climate action around responsibility – giving the climate movement a clearer moral vision.

Standing Rock brought together the largest gathering of Indigenous nations in over a century, joined by military veterans, climate activists and faith leaders in an unprecedented show of solidarity. These alliances didn’t dilute anyone’s message; they built power, broadened reach, and connected struggles against shared systems of domination.

As pattrice jones argues, solidarity across movements is not just morally right – it’s strategically necessary. We cannot change the narrative about animal freedom as a legitimate freedom struggle by remaining isolated. But we can help change it by showing up in diverse social justice spaces, by having difficult yet respectful conversations, by listening deeply, by bridging seeming divides, and by deepening connections with other movements – however unlikely those connections might seem.

“We’re working to dismantle a 10,000-year-old story that says domination is natural.” Inlay frieze with limestone figures. A Sumerian scene showing milking cows and making dairy products. From the facade of the Temple of Ninhursag at Tell al-'Ubaid, Iraq. Early Dynastic period, 2800-2600 BCE. On display at the Sumerian Gallery of the Iraq Museum in Baghdad, Iraq. TO 303 (excavation numbers). Excavated in 1923.

What are we pushing for?

So what is our movement really pushing for? Not only vital legal protections for other animals. Not only an end to factory farming. We’re working to dismantle a 10,000-year-old story that says domination is natural, that some lives matter less than others, that we exist separate from and superior to the rest of the living world.

We’re here to help humanity remember what we knew for 200,000 years: that we are connected with our animal cousins and the rest of nature. This isn’t romanticism or nostalgia. It’s acknowledging what the science of ecology, evolutionary biology, and even neuroscience now confirm: we are interdependent with all life. Our wellbeing is inseparable.

Some might dismiss this approach as too soft, too sentimental, too ‘feminine’. But that reaction reveals a key part of the problem: we’ve been taught to see connection as weakness and emotional distance as strength; to dismiss care as naïve and utilitarian logic as rational. These binaries are part of the same system that ranks humans over other animals, men over women, reason over emotion, culture over nature. Dismantling and rebalancing these binaries isn’t ‘soft’ work – it’s the hardest, most essential work in building a different kind of society.

Yes, all this is complex, vast and largely unknown. But perhaps a necessary step is helping people see that animal freedom and human freedom aren’t separate struggles; they’re both built on the violent fiction that some beings exist for the benefit of others.

Until we can pull back the curtain on this human-made hierarchy, help people understand its origins and costs, and offer a different path forward, society – and even social justice movements – will inevitably keep reproducing it.

This doesn’t mean every animal advocate must work intersectionally, or that every action needs to address multiple oppressions. It means recognising that the framework keeping other animals at the bottom of the hierarchy is the same one keeping marginalised humans there too.

We need every approach, every strategy, every role in our movement. We need people focused on immediate harm reduction, and people building towards long-term narrative change. We need people working within systems, and people imagining beyond them. We need people focused solely on animal issues, and others focused on building cross-movement solidarity. This is what a diverse and healthy movement ecosystem looks like.

What matters is whether we can stay grounded to a deeper truth and a bigger story: That animal freedom is part of a shared freedom, and that freedom is about reconnecting with who we really are and how we all belong.

Believing human freedom must be addressed before animal freedom, or that animal freedom can only be discussed in isolation, unintentionally reinforces the same hierarchy all social justice movements are trying to dismantle. Perhaps the deepest act of resistance is refusing to reproduce it.